Contract is probably the most familiar legal concept in our society because it is so central to our political, economic, and social life. So commonplace is the concept of contract—and our freedom to make contracts with each other—that it is difficult to imagine a time when contracts were rare, when people’s everyday associations with one another were not freely determined.

Yet in historical terms, it was not so long ago that contracts were rare, entered into by very few: that affairs should be ordered based on mutual assent was mostly unknown. In primitive societies and in feudal Europe, relationships among people were largely fixed; traditions spelled out duties that each person owed to family, tribe, or manor. People were born into an ascribed position—a status (not unlike the caste system still existing in India)—and social mobility was limited. Sir Henry Maine, a nineteenth-century British historian, wrote that “the movement of the progressive societies has…been a movement from status to contract.” This movement was not accidental—it developed with the emerging industrial order. From the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, England evolved into a booming mercantile economy, with flourishing trade, growing cities, an expanding monetary system, the commercialization of agriculture, and mushrooming manufacturing. This evolution necessitated the creation of contract law.

Contract law did not develop according to a conscious plan, however , but i t was a response to changing conditions . Not until the nineteenth century, in both the United States and England, did a full-fledged judge-made law of contracts arise together with, and help create, modern capitalism. Today, the contract determine s the nature of most economic transaction s .

In An Economic Analysis of Law , Judge Richard A. Posner (a former University of Chicago law professor) suggests that contract law performs three significant economic functions. First, it helps maintain incentives for individuals to exchange goods and services efficiently. Second, it reduces the costs of economic transactions because its very existence means that the parties need not go to the trouble of negotiating a variety of rules and terms already spelled out. Third, the law of contracts alerts the parties to troubles that have arisen in the past, thus making it easier to plan the transactions more intelligently and avoid potential pitfalls.

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts (Section 1) says, “A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty.” Similarly, the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) says, “‘Contract’ means the total legal obligation which results from the parties’ agreement as affected by this Act and any other applicable rules of law.” As operational definitions, these two are circular; in effect, a contract is defined as an agreement that the law will hold the parties to.

Most simply, a contract is a legally enforceable promise between two or more parties . N ot every promise or agreement creates a binding contract , so a contract requires more than just an agreement. The law of contracts takes into account the way in which contracts are made, by whom they are made, and for what purposes they are made.

Although contract law has many nuances, it consists of several principal inquiries, each of which will be taken up in subsequent Chapters .

Did the parties create a valid contract? One party to a contract must make a clear and unequivocal offer to the other party which in turn must accept the offer without any conditions or changes. Each party must exchange something of value (consideration) with the other party. Both parties must have the legal capacity to enter into a contract. And finally, the contract must be for a lawful purpose.

Did the parties intend to enter a valid contract? Both parties must have a genuine intent to create a legally binding agreement. If it turns out that one or both parties did not have the requisite intent, the attempt at contract may not be valid.

Do we know what the contract means and can it be carried out? Many contracts can be oral, but s ometimes contracts need to be in writing (or evidenced by some writing), or they can’t be enforced. If the terms of a contract are unclear, a court has to interpret the contract, or it can’t be enforced.

Do persons other than the contracting parties have rights or duties under the contract? Sometimes third parties may have rights in the contracts of others, and so we must determine if any other parties have rights in the contract that is under review.

How do we know when the contract has come to an end? A contract can be terminated with performance, without performance, and sometimes a contract may be breached. A contract that is not fully performed may have remedies available , and we will study how those remedies will be assigned and calculated.

Together, the answers to the questions outlined above determine the rights and obligations of contracting parties.

The most important sources of contract law are state case law and state statutes (though there are also many federal statutes governing how contracts are made by and with the federal government).

Law made by judges is called case law . Because contract law was made up in the common-law courtroom by individual judges as they applied rules to resolve disputes before them, it grew over time to formidable proportions. Because of this, much of U.S. contract law is rooted in common law principles. Common law is law that has developed over time through judicial decisions in individual contract disputes and claims. Courts in the United States have issued rulings in contract-related cases for centuries, creating a body of precedent that serves as the foundation of contract law. Thus, by the early twentieth century, tens of thousands of contract disputes had been submitted to the courts for resolution, and the published opinions written by judges , if collected in one place, would have filled dozens of bookshelves. Clearly this mass of material was too unwieldy for efficient use. A similar problem also had developed in the other leading branches of the common law.

Disturbed by the plethora of cases , the difficulty in finding a specific case, and the resulting uncertainty of the law, a group of prominent American judges, lawyers, and law teachers founded the American Law Institute (ALI) in 1923 to attempt to clarify, simplify, and improve the law. One of the ALI’s first projects, and ultimately one of its most successful, was the drafting of the Restatement of the Law of Contracts , completed in 1932. A revision—the Restatement (Second) of Contracts—was undertaken in 1964 and completed in 1979. Hereafter, references to “the Restatement” pertain to the Restatement (Second) of Contracts.

The Restatements (they also exist in the other fields of law besides contracts, including torts and property) are detailed analyses of the decided cases in each field. Encompassing a wide range of disciplines, the Restatements summarize the common law principles as they have evolved across the majority of U.S. jurisdictions. In addition to presenting common law doctrines, the Restatements offer commentary, hypothetical scenarios illustrating the application of these principles, and summaries of relevant cases.

The Restatement won prompt respect in the courts and has been cited in innumerable cases. The Restatements are not authoritative, in the sense that they are not actual judicial precedents; but they are nevertheless weighty interpretive texts, and judges frequently look to them for guidance. They are as close to “black letter” rules of law as exist anywhere in the American common-law legal system.

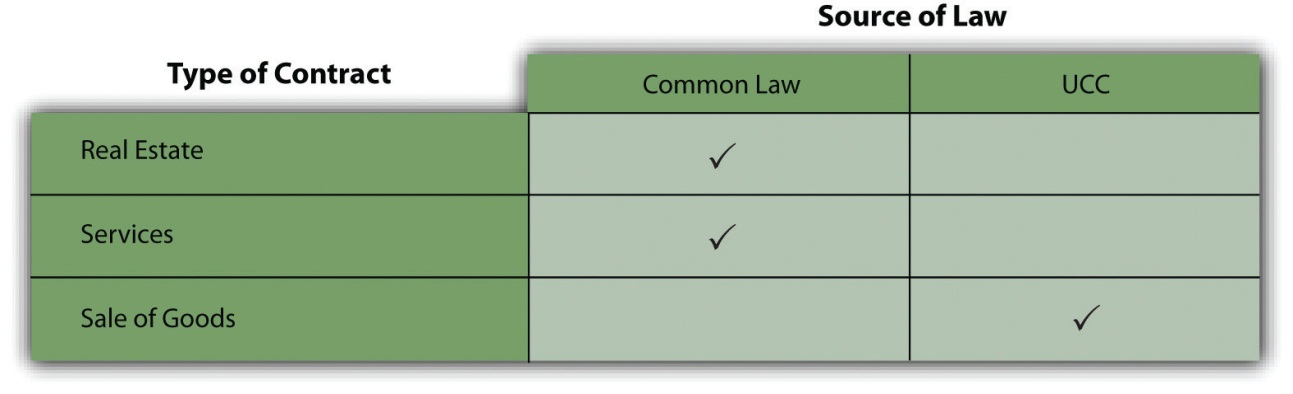

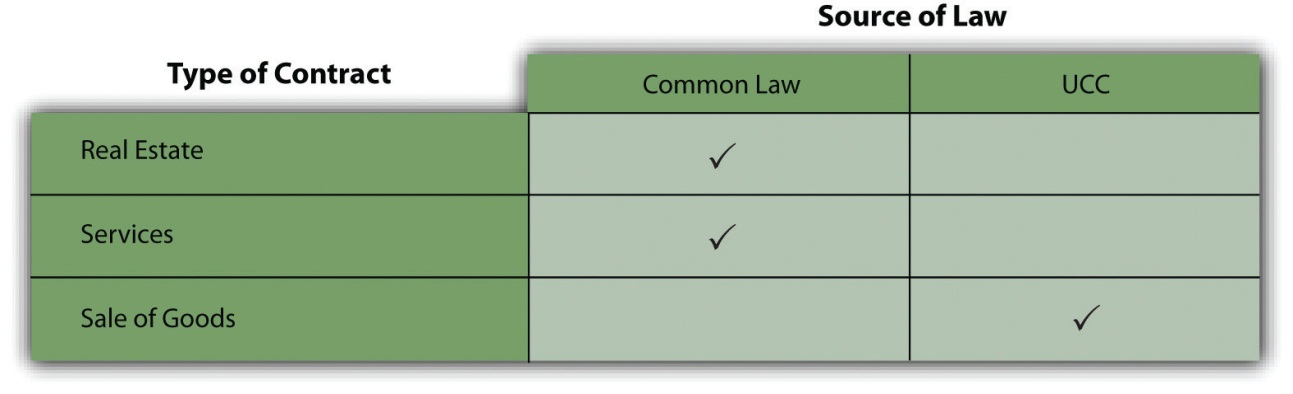

Today, c ommon law or case law (the terms are mostly synonymous) governs contracts for the sale of real estate and services. “Services” refers to acts or deeds (like plumbing, drafting documents, driving a car) as opposed to the sale of property.

Common-law contract principles govern contracts for real estate and services. Because of the historical development of the English legal system, contracts for the sale of goods came to be governed by a different body of legal rules. In its modern American manifestation, that body of rules is an important statute: the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) , especially Article 2 , which deals with the sale of goods.

In addition to the overabundance of cases that was discussed above, in commercial transactions there was an another barrier to legal efficiency in contracting. The development of the common law through judicial interpretation meant that the law varied, some times greatly, from state to state. This was a serious impediment to business as the American economy became nationwide during the twentieth century. Although there had been some uniform laws concerned with commercial deals—including the Uniform Sales Act, first published in 1906—few were widely adopted and none nationally.

Enter the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). The UCC is a model law developed by the ALI and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws; it has been adopted in one form or another by the legislatures in all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and the American territories. It is a “national” law not enacted by Congress—it is not federal law but uniform state law.

Initial drafting of the UCC began in 1942 and was ten years in the making, involving the efforts of hundreds of practicing lawyers, law teachers, and judges. A final draft, promulgated by the ALI, was endorsed by the American Bar Association and published in 1951. Various revisions followed in different states, threatening the uniformity of the UCC. The ALI responded by creating a permanent editorial board to oversee future revisions. In one or another of its various revisions, the UCC has been adopted in whole or in part in all American jurisdictions. The UCC is now a basic law of relevance to every business and business lawyer in the United States, even though it is not entirely uniform because different states have adopted it at various stages of its evolution—an evolution that continues still.

The UCC consists of nine major substantive articles, each dealing with separate though related subjects. The articles are as follows:

Article 2 deals with the sale of goods, which the UCC defines as “all things…which are movable at the time of identification to the contract for sale other than the money in which the price is to be paid.” As these sales/leases are accomplished by contracting, agreements covered by Article s 2 /2A which relat e to the present or future sale of goods also make up the law of contracts.

Figure 5.1 Sources of Law

A Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) was approved in 1980 at a diplomatic conference in Vienna. (A convention is a preliminary agreement that serves as the basis for a formal treaty.) The CISG has been adopted by more than forty countries, including the United States.

The CISG is significant for three reasons. First, it is a uniform law governing the sale of goods—in effect, an international Uniform Commercial Code. The major goal of the drafters was to produce a uniform law acceptable to countries with different legal, social, and economic systems. Second, although provisions in the CISG are generally consistent with the UCC, there are significant differences. For instance, under the CISG, consideration is not required to form a contract, and there is no Statute of Frauds (a requirement that certain contracts be evidenced by a writing). Third, the CISG represents the first attempt by the U.S. Senate to reform the private law of business through its treaty powers, for the CISG preempts the UCC. The CISG is not mandatory; parties to an international contract for the sale of goods may choose to have their agreement governed by different law, perhaps the UCC, or, say, Japanese contract law. The CISG does not apply to contracts for the sale of (1) ships or aircraft, (2) electricity, or (3) goods bought for personal, family, or household use, nor does it apply (4) where the party furnishing the goods does so only incidentally to the labor or services part of the contract.

The objective theory of contracts is a fundamental principle in contract law that focuses on the objective intent of the parties involved in a contract rather than their subjective beliefs or intentions. Using the objective theory of contracts, a contract is formed based on the outward, objective manifestations of the parties’ intentions, as perceived by a reasonable person. In other words, it’s not necessary for the parties to share the same internal, subjective understanding of the contract terms; what matters is how their words and actions would be reasonably understood by an outside observer. This standard takes into account the parties’ communications, actions, and conduct leading up to and including the time of the contract’s formation. Courts will therefore look at the objective evidence of the parties’ intent, rather than their individual, subjective beliefs or unexpressed intentions. This means that even if one party secretly harbored a different intention, the contract is based on what they objectively conveyed to the other party. The objective theory of contracts promotes clarity and predictability in contract law and provides a foundation for enforcing agreements based on the parties’ objective expressions of intent.

Contracts are classified in different ways. Ascribing a classification to a contract helps to learn about that contract, and potential rights and obligations under that contract. This section will describe the primary ways that contracts are classified.

A contract is either express, implied-in-fact (implied) or imposed by the court as an implied in law contract (quasi).

An express contract is a contract in which the terms and conditions are explicitly stated, either orally or in writing, with the intent of both parties to enter a contract. It’s a clear and definite agreement between the parties. For example, a homeowner hires a plumber to fix a leaky hose fixture outside their house. The homeowner and the plumber have a written agreement that outlines the specific terms of the plumbing service, such as the scope of work, the cost, and the timeline for completion. Even if neither party signs the document, this would still be an express contract, as the agreement is clearly expressed in words.

An implied contract is a contract in which the agreement is not explicitly stated in words but is inferred from the conduct and actions of the parties involved. An implied contract between the homeowner and the plumber could arise if the homeowner calls the plumber and the plumber performs the work, fixing the leaky hose fixture outside the house without discussing specific terms of the agreement. Clearly, both parties intended for the plumber to be paid for any work completed, but the detailed understanding between the two parties was not directly discussed, resulting in an implied contract.

Unlike both express and implied contracts, which embody an actual agreement of the parties, a quasi contract does not arise from the agreement of the parties. In fact, there is a lack of agreement in quasi contract situations. This is why a quasi contract is an obligation said to be “imposed by law” in order to avoid unjust enrichment of one person at the expense of another. In other words, it is an obligation imposed by a judge to prevent injustice, and not a contract at all. Suppose, for example, that a local plumbing company mistakenly sends a plumber to your house, thinking it belongs to the neighbor on the next block who had called for a repair to the leaky hose outside their house. On arrival to your home, the plumber actually does find a leaking hose and fixes it while you are home. You never communicated with the plumbing company even though you saw the repair taking place. Although it is true there is no contract, the law implies a contract for the value of the material: of course you will have to pay for the service you received.

Roger’s Backhoe Service, Inc. v. Nichols, 681 N.W.2d 647 (Iowa 2004)

Defendant, Jeffrey S. Nichols, is a funeral director in Muscatine.…In early 1998 Nichols decided to build a crematorium on the tract of land on which his funeral home was located. In working with the Small Business Administration, he was required to provide drawings and specifications and obtain estimates for the project. Nichols hired an architect who prepared plans and submitted them to the City of Muscatine for approval. These plans provided that the surface water from the parking lot would drain onto the adjacent street and alley and ultimately enter city storm sewers. These plans were approved by the city.

Nichols contracted with Roger’s [Backhoe Service, Inc.] for the demolition of the foundation of a building that had been razed to provide room for the crematorium and removal of the concrete driveway and sidewalk adjacent to that foundation. Roger’s completed that work and was paid in full.

After construction began, city officials came to the jobsite and informed Roger’s that the proposed drainage of surface water onto the street and alley was unsatisfactory. The city required that an effort be made to drain the surface water into a subterranean creek, which served as part of the city’s storm sewer system. City officials indicated that this subterranean sewer system was about fourteen feet below the surface of the ground.…Roger’s conveyed the city’s mandate to Nichols when he visited the jobsite that same day.

It was Nichols’ testimony at trial that, upon receiving this information, he advised…Roger’s that he was refusing permission to engage in the exploratory excavation that the city required. Nevertheless, it appears without dispute that for the next three days Roger’s did engage in digging down to the subterranean sewer system, which was located approximately twenty feet below the surface. When the underground creek was located, city officials examined the brick walls in which it was encased and determined that it was not feasible to penetrate those walls in order to connect the surface water drainage with the underground creek. As a result of that conclusion, the city reversed its position and once again gave permission to drain the surface water onto the adjacent street and alley.

[T]he invoices at issue in this litigation relate to charges that Roger’s submitted to Nichols for the three days of excavation necessary to locate the underground sewer system and the cost for labor and materials necessary to refill the excavation with compactable materials and attain compaction by means of a tamping process.…The district court found that the charges submitted on the…invoices were fair and reasonable and that they had been performed for Nichols’ benefit and with his tacit approval.…

The court of appeals…concluded that a necessary element in establishing an implied-in-fact contract is that the services performed be beneficial to the alleged obligor. It concluded that Roger’s had failed to show that its services benefited Nichols.…

In describing the elements of an action on an implied contract, the court of appeals stated in [Citation], that the party seeking recovery must show:

(1) the services were carried out under such circumstances as to give the recipient reason to understand:

(a) they were performed for him and not some other person, and

(b) they were not rendered gratuitously, but with the expectation of compensation from the recipient; and

(2) the services were beneficial to the recipient.

In applying the italicized language in [Citation] to the present controversy, it was the conclusion of the court of appeals that Roger’s’ services conferred no benefit on Nichols. We disagree. There was substantial evidence in the record to support a finding that, unless and until an effort was made to locate the subterranean sewer system, the city refused to allow the project to proceed. Consequently, it was necessary to the successful completion of the project that the effort be made. The fact that examination of the brick wall surrounding the underground creek indicated that it was unfeasible to use that source of drainage does not alter the fact that the project was stalemated until drainage into the underground creek was fully explored and rejected. The district court properly concluded that Roger’s’ services conferred a benefit on Nichols.…

Decision of court of appeals vacated; district court judgment affirmed.

Case questions

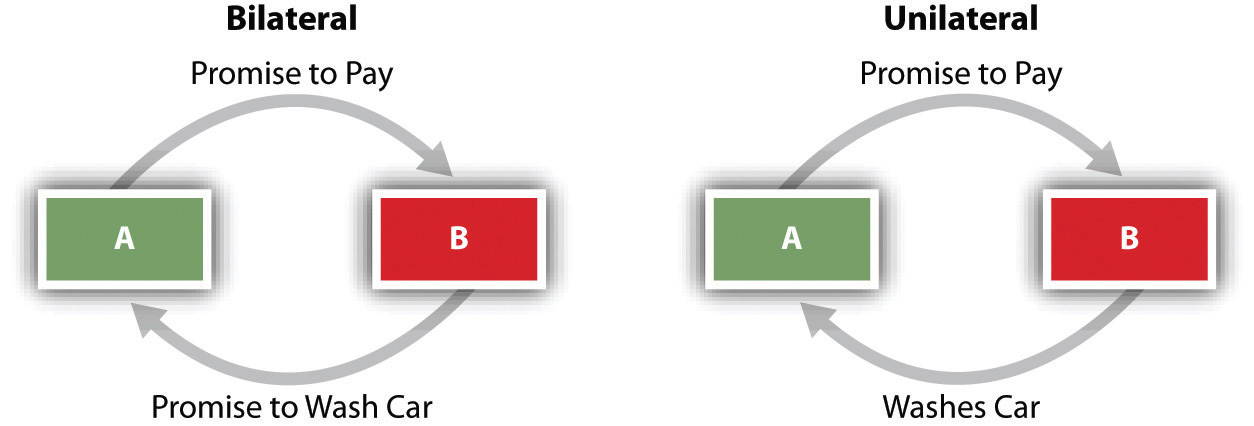

The typical contract is one in which both parties make mutual promises. Each is both promisor and promisee; that is, each pledges to do something, and each is the recipient of such a pledge. This type of contract is called a bilateral contract . The example above where the homeowner and the plumber enter a contract with express terms to fix the leaky fixture outside the house also illustrates a bilateral contract. The homeowner has offered payment, and the plumber has promised the repair.

A unilateral contract is a contract where one party makes a promise and the other party can accept that promise only by performing a specific act. Unilateral contracts are as valid as bilateral contracts. Suppose that the homeowner puts a sign on their lawn that says “I will pay $100 to the first person to fix the leaky fixture outside my home.” A plumber sees the sign, says nothing, but goes to the pipe, gets to work, and repairs the leak. This is a unilateral contract. In a unilateral contract, the acceptance of the promise is indicated through performance, rather than by making a reciprocal promise.

Figure 5.2 Bilateral and Unilateral Contracts

Woolley v. Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., 491 A.2d 1257 (N.J. 1985)

Plaintiff, Richard Woolley, was hired by defendant, Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., in October 1969, as an Engineering Section Head in defendant’s Central Engineering Department at Nutley. There was no written employment contract between plaintiff and defendant. Plaintiff began work in mid-November 1969. Sometime in December, plaintiff received and read the personnel manual on which his claims are based.

[The company’s personnel manual had eight pages;] five of the eight pages are devoted to “termination.” In addition to setting forth the purpose and policy of the termination section, it defines “the types of termination” as “layoff,” “discharge due to performance,” “discharge, disciplinary,” “retirement” and “resignation.” As one might expect, layoff is a termination caused by lack of work, retirement a termination caused by age, resignation a termination on the initiative of the employee, and discharge due to performance and discharge, disciplinary, are both terminations for cause. There is no category set forth for discharge without cause. The termination section includes “Guidelines for discharge due to performance,” consisting of a fairly detailed procedure to be used before an employee may be fired for cause. Preceding these definitions of the five categories of termination is a section on “Policy,” the first sentence of which provides: “It is the policy of Hoffmann-La Roche to retain to the extent consistent with company requirements, the services of all employees who perform their duties efficiently and effectively.”

In 1976, plaintiff was promoted, and in January 1977 he was promoted again, this latter time to Group Leader for the Civil Engineering, the Piping Design, the Plant Layout, and the Standards and Systems Sections. In March 1978, plaintiff was directed to write a report to his supervisors about piping problems in one of defendant’s buildings in Nutley. This report was written and submitted to plaintiff’s immediate supervisor on April 5, 1978. On May 3, 1978, stating that the General Manager of defendant’s Corporate Engineering Department had lost confidence in him, plaintiff’s supervisors requested his resignation. Following this, by letter dated May 22, 1978, plaintiff was formally asked for his resignation, to be effective July 15, 1978.

Plaintiff refused to resign. Two weeks later defendant again requested plaintiff’s resignation, and told him he would be fired if he did not resign. Plaintiff again declined, and he was fired in July.

Plaintiff filed a complaint alleging breach of contract.…The gist of plaintiff’s breach of contract claim is that the express and implied promises in defendant’s employment manual created a contract under which he could not be fired at will, but rather only for cause, and then only after the procedures outlined in the manual were followed. Plaintiff contends that he was not dismissed for good cause, and that his firing was a breach of contract.

Defendant’s motion for summary judgment was granted by the trial court, which held that the employment manual was not contractually binding on defendant, thus allowing defendant to terminate plaintiff’s employment at will. The Appellate Division affirmed. We granted certification.

The employer’s contention here is that the distribution of the manual was simply an expression of the company’s “philosophy” and therefore free of any possible contractual consequences. The former employee claims it could reasonably be read as an explicit statement of company policies intended to be followed by the company in the same manner as if they were expressed in an agreement signed by both employer and employees.…

This Court has long recognized the capacity of the common law to develop and adapt to current needs.…The interests of employees, employers, and the public lead to the conclusion that the common law of New Jersey should limit the right of an employer to fire an employee at will.

In order for an offer in the form of a promise to become enforceable, it must be accepted. Acceptance will depend on what the promisor bargained for: he may have bargained for a return promise that, if given, would result in a bilateral contract, both promises becoming enforceable. Or he may have bargained for some action or nonaction that, if given or withheld, would render his promise enforceable as a unilateral contract. In most of the cases involving an employer’s personnel policy manual, the document is prepared without any negotiations and is voluntarily distributed to the workforce by the employer. It seeks no return promise from the employees. It is reasonable to interpret it as seeking continued work from the employees, who, in most cases, are free to quit since they are almost always employees at will, not simply in the sense that the employer can fire them without cause, but in the sense that they can quit without breaching any obligation. Thus analyzed, the manual is an offer that seeks the formation of a unilateral contract—the employees’ bargained-for action needed to make the offer binding being their continued work when they have no obligation to continue.

The unilateral contract analysis is perfectly adequate for that employee who was aware of the manual and who continued to work intending that continuation to be the action in exchange for the employer’s promise; it is even more helpful in support of that conclusion if, but for the employer’s policy manual, the employee would have quit. See generally M. Petit, “Modern Unilateral Contracts,” 63 Boston Univ. Law Rev. 551 (1983) (judicial use of unilateral contract analysis in employment cases is widespread).

…All that this opinion requires of an employer is that it be fair. It would be unfair to allow an employer to distribute a policy manual that makes the workforce believe that certain promises have been made and then to allow the employer to renege on those promises. What is sought here is basic honesty: if the employer, for whatever reason, does not want the manual to be capable of being construed by the court as a binding contract, there are simple ways to attain that goal. All that need be done is the inclusion in a very prominent position of an appropriate statement that there is no promise of any kind by the employer contained in the manual; that regardless of what the manual says or provides, the employer promises nothing and remains free to change wages and all other working conditions without having to consult anyone and without anyone’s agreement; and that the employer continues to have the absolute power to fire anyone with or without good cause.

Reversed and remanded for trial.

Case questions